The term “incunabula” [in-kyoo-nab-yuh-luh] signifies the first generation of books produced in western Europe using movable type. Johannes Gutenberg’s bible, the signal achievement which heralded the advent of movable type among Europeans, rolled off his printing press in 1455. Later scholars settled on the entirely arbitrary date of January 1, 1501, as the cutoff point for incunabula: those produced after Gutenberg and before 1/1/1501 were outfitted with the fancy incunabula designation, and those produced on or after after that date were, for the most part, simply considered plain ol’ books.

Thus, incunabula hold a special place in the hearts of many collectors of fine and rare books. Carl Weeks, who certainly numbered among the finest collectors of his day, acquired several examples of incunabula for his Library collection.

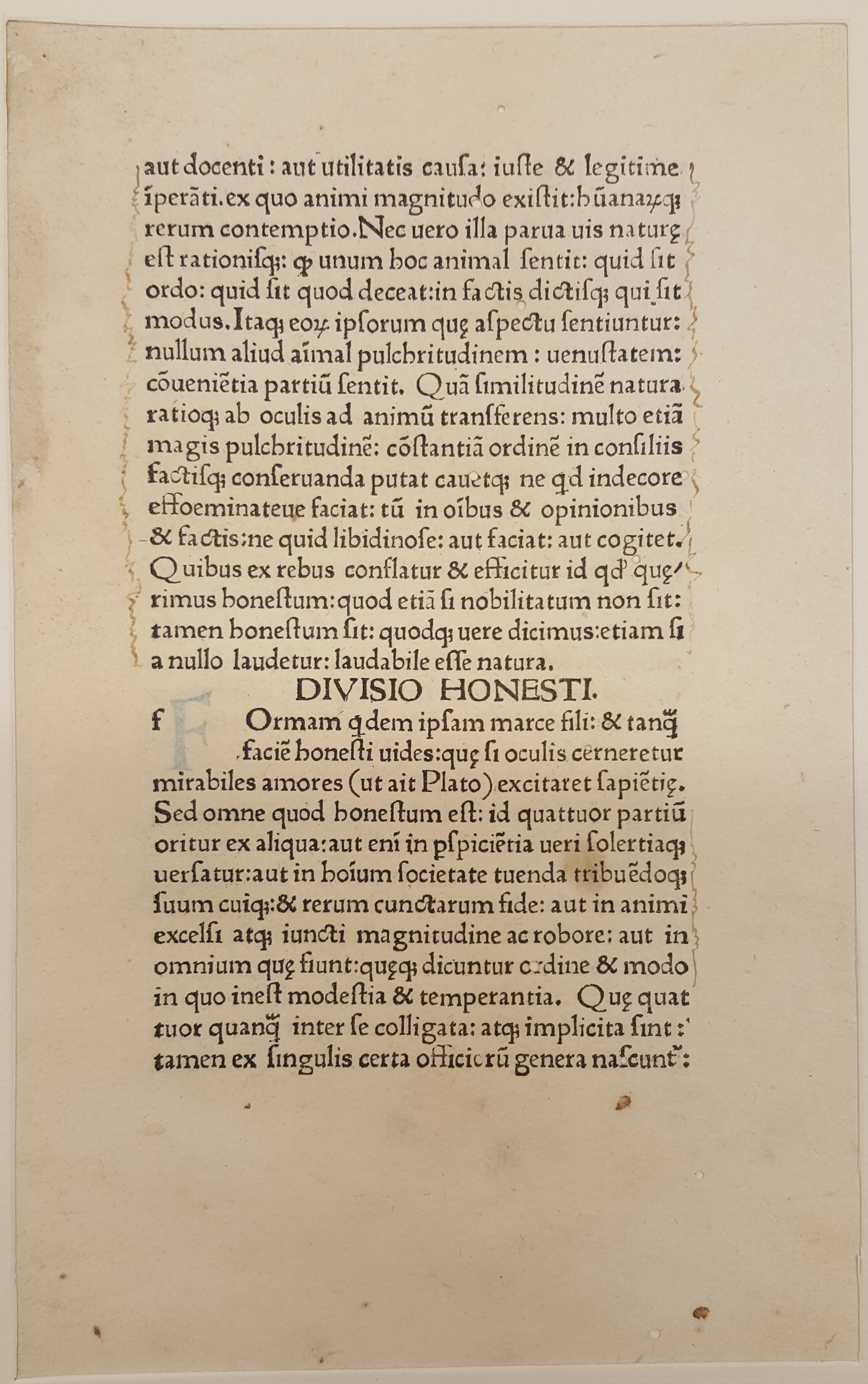

Let’s start at the very beginning – a very good place to start, as Maria Von Trapp once said. Here, in all its fifteenth-century glory, is our Gutenberg bible leaf. Carl Weeks acquired this piece from New York book dealer Gabriel Wells in the 1920s.

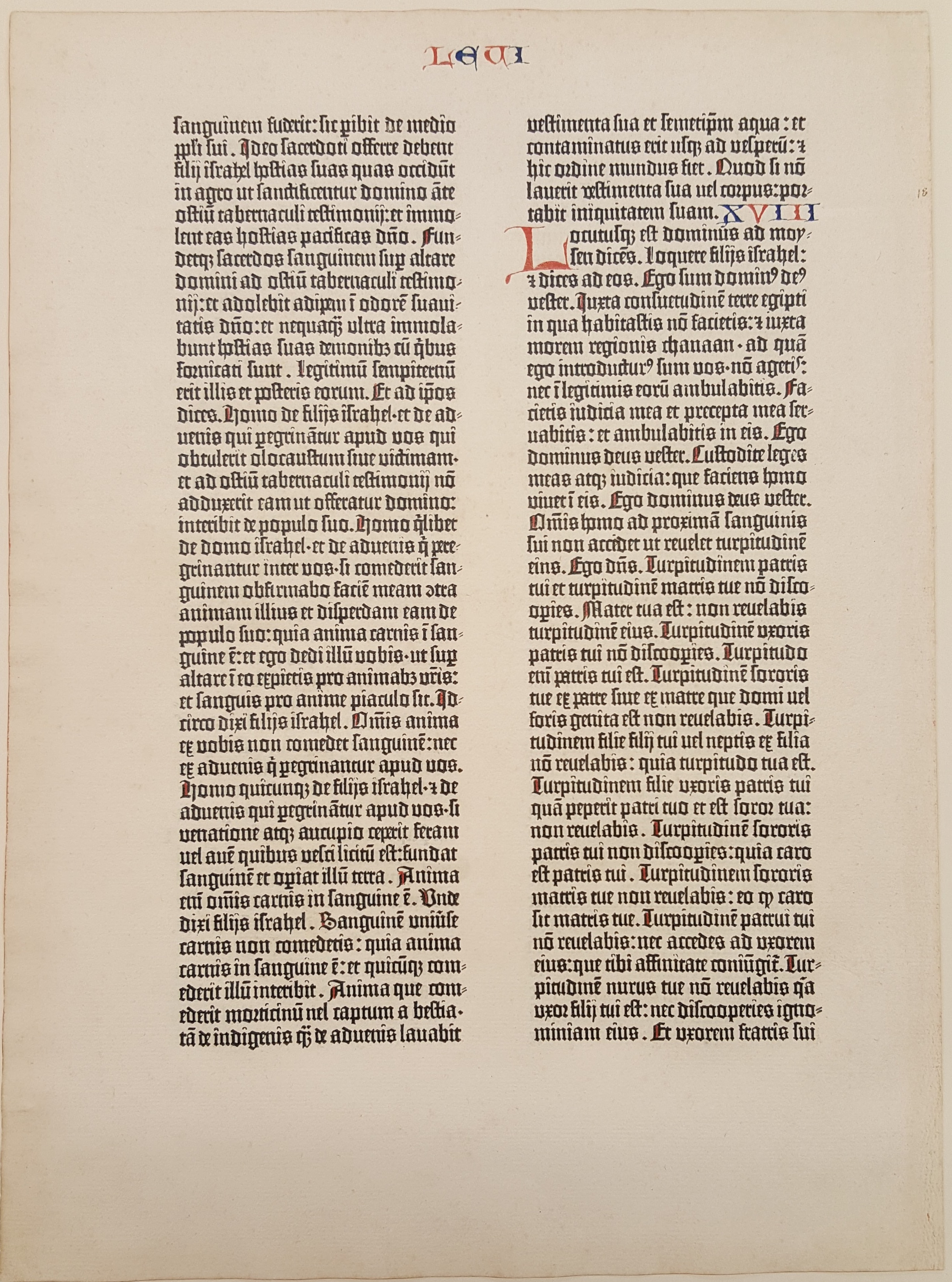

Gutenberg worked primarily in Mainz, a city in modern-day Germany. Soon thereafter a robust trade in printing emerged in Venice, where deep Italian pockets bankrolled book production for generations. Two Bavarian brothers, John and Wendelin de Spire, established one of the first presses in Venice in 1469. The incunabula leaf pictured here was printed by Wendelin in 1472 and is from an edition of Cicero’s On Duty.

Back at Strassburg in 1472, Johann Mentelin was hard at work on a mammoth production of Nicholas of Lyra’s Postilla super totam Bibliam, which was the first major work of commentary on the bible. Some accounts suggest that Mentelin learned his craft from Gutenberg himself. At any rate, the book produced by Mentelin is a show-stopper. It includes decorated capitals, rubrication, innovative design and, delightfully, annotations from some long-ago reader.

Venice in 1475 was a wonderful confluence of geography and talent: in addition to the de Spire brothers, Nicolas Jensen, roundly considered one of history’s greatest printers and typographers, turned out beautiful volumes from his Venetian workshop. The leaf pictured is from Jensen’s edition of Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Philosophers remains representative of his incomparable design and execution.

The works of Thomas Aquinas, the prolific Roman Catholic priest, philosopher, and theologian, proved a popular subject for many early printers. Anton Koberger, who established the first printing press in Nuremberg in 1470, produced in 1475 a gorgeous edition of Aquinas’ Catena aurea in quatuor Evangelia (basically, a commentary on the four Gospels). The opening page of the book is a stunner.

One of the most frequently-reproduced books of the Middle Ages, The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, chronicled the exploits of several Roman Catholic saints. In 1480, the Italian printer Antonio de Strata published a version of Voragine’s work in Venice.

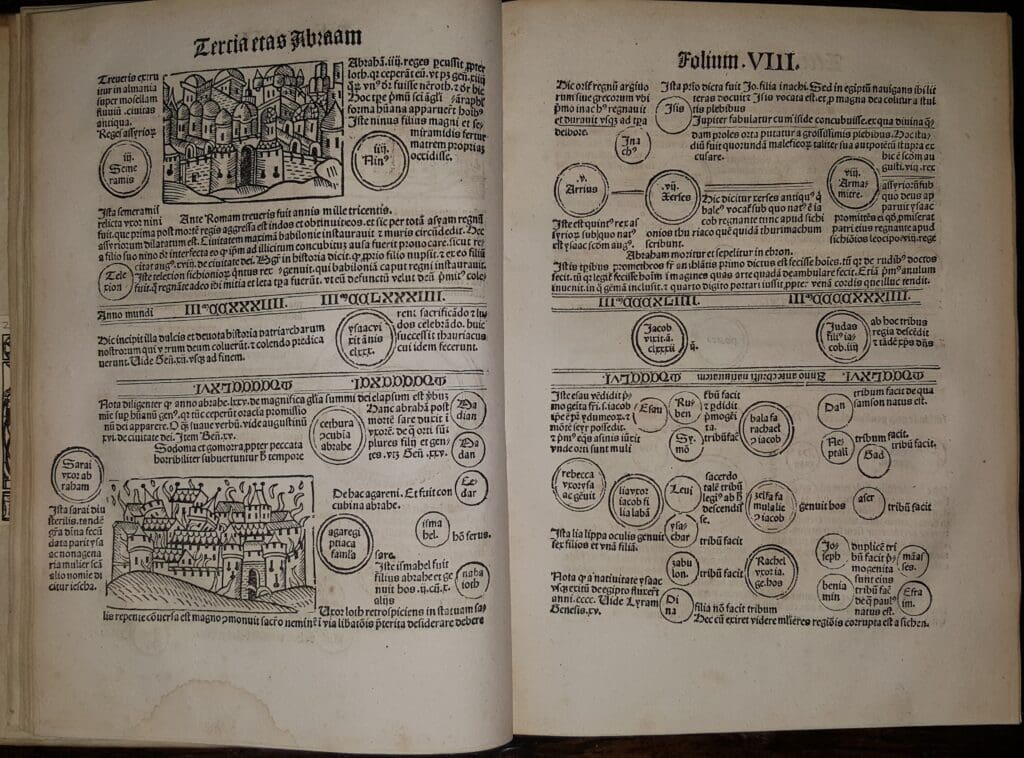

The second-oldest book in the Salisbury House collection, and our oldest complete bible, had its origins in Venice as well. Johannes Herbort de Seligenstadt was a German printer who worked first in Padua in 1475 and moved to Venice six years later. He ultimately issued three editions of the bible; the version at Salisbury House dates to 1483.

If commentaries on the obscurities of 13th-century canon law really blow your hair back, then this next incunabulum is for you. It’s an edition of Bernardus Parmensis’ exegesis of the Decretals of (Pope) Gregory IX printed in 1487.

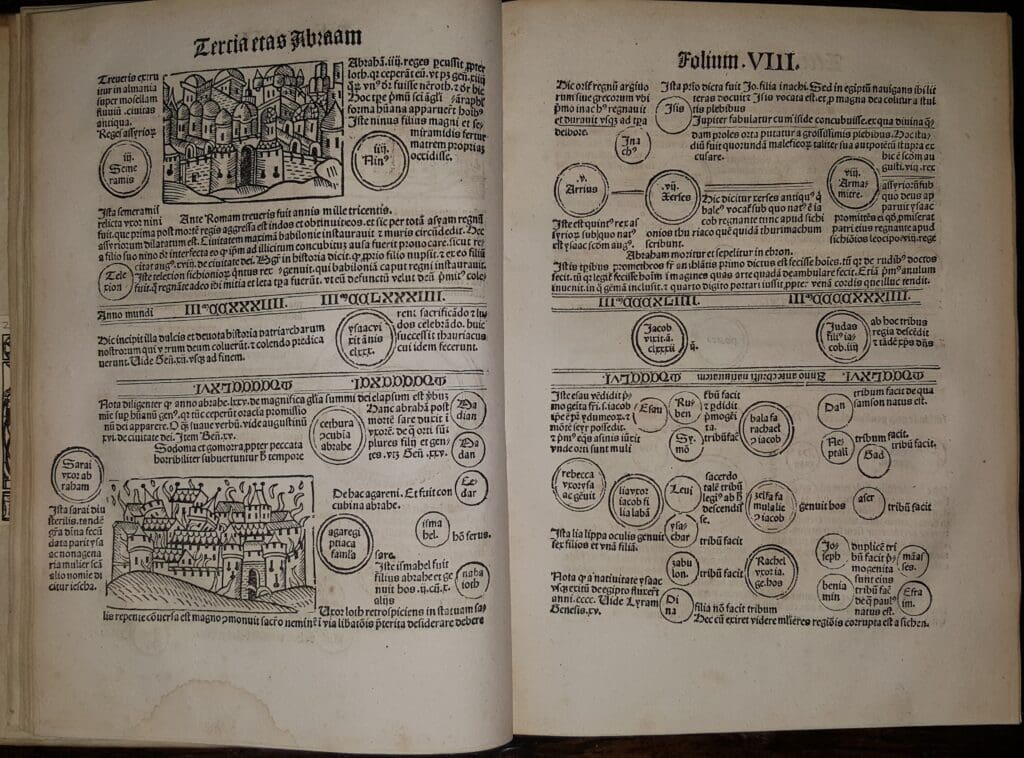

Typically, the authors of most books printed during the incunabula period were already dead. Werner Rolewinck was one of the few exceptions. His Fasciculus temporum combined secular history with biblical history and commentary. This edition was published in Strassburg in 1490, likely by Johann Pruss.

Dante Alighieri’s Divina Commedia, completed in 1320, remains a classic in world literature. This incunabula leaf is part of the complete Divina Commedia printed in Venice by Petrus de Piasio in 1491.

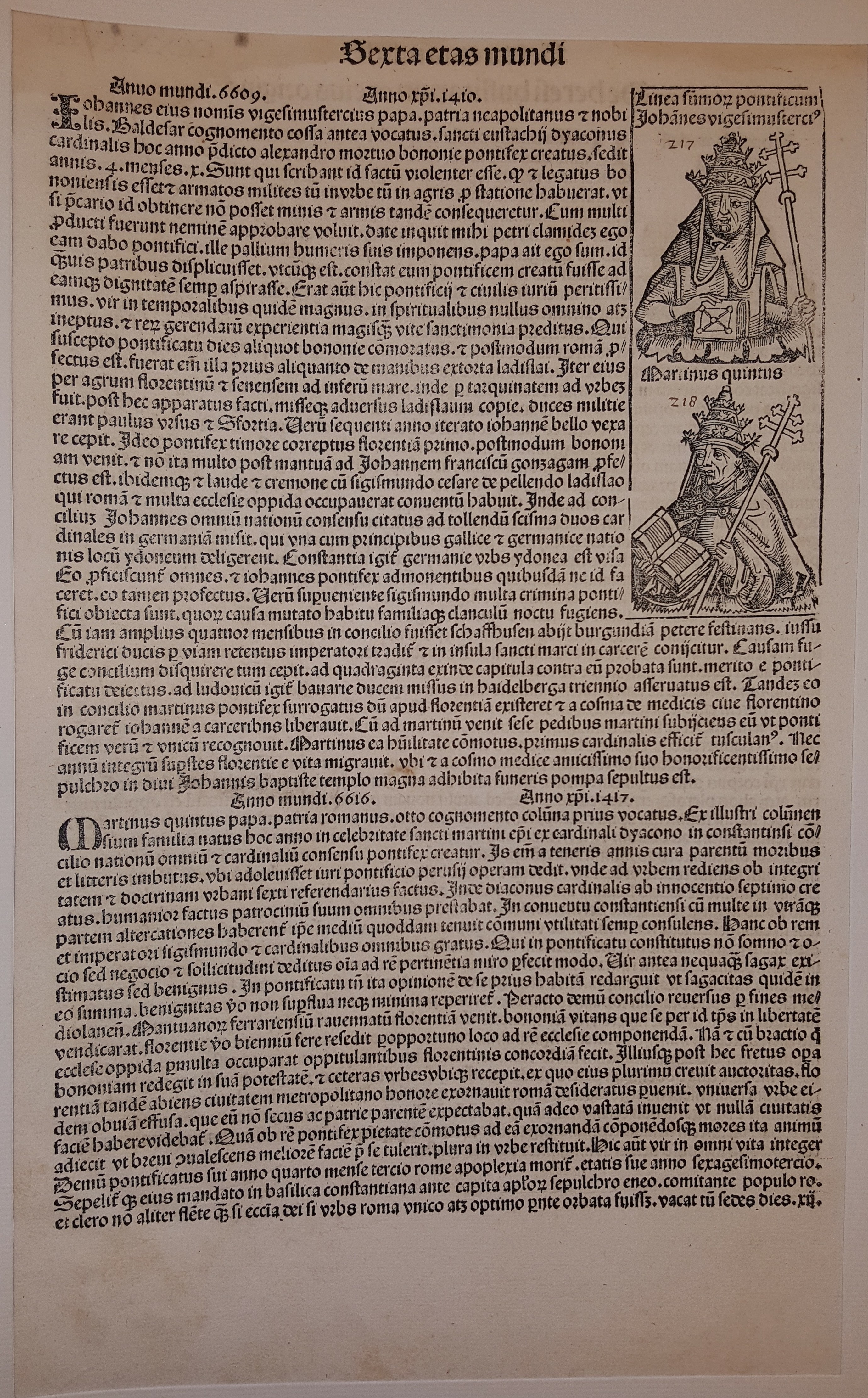

Anton Koberger, the prolific printer of Nuremberg, offered for sale in 1493 one of the most richly illustrated works of the incunabula period. His edition of Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle continues to be roundly considered one of the finest works of this era.

The last of Carl Weeks’ incunabula collection dates to 1496. The Epistolae Sancti Hieronymi, or the letters of St. Jerome, rolled off the Venetian press of Johannes Rubeus Vercellensis in 1496. Interestingly, the book was printed to include rubrication and illustrated capitals; however, our edition only includes the blank spaces where these additional decorative elements would have been added.

Note: The Salisbury House Library Collection is now housed at Grinnell College where it is being digitized and studied. If you would like to learn more about the collection, check out the Special Collections Website.